PHOTO BY MICHAEL PATRICK // BUY THIS PHOTO

The Kingston Fossil plant is running now at reduced capacity, as seen by its two huge primary stacks sitting idle while a smaller stack belches smoke Thursday, Sep. 30, 2010. Coal is under seige as an industry as utilities such as TVA, driven by tightening government regulations on emissions, are scaling back on the use of coal-fired power plants.

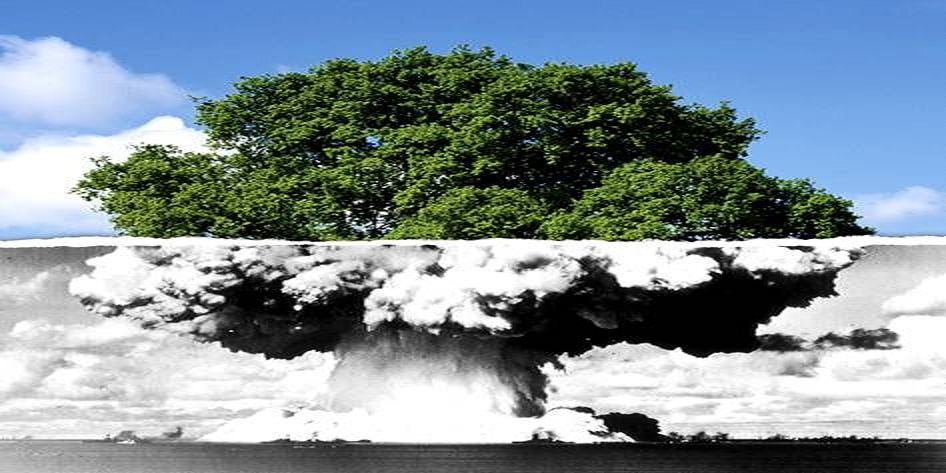

Sunny days appear to be ahead for green energy in Tennessee, but the coal industry faces a future clouded by a number of issues such as declining demand because of environmental concerns and the resurgence of nuclear power.

Utilities like TVA are the primary customers for coal companies, and TVA recently announced a strategic shift away from coal and toward more sustainable energy sources for its power plants. It already plans to idle nine coal-fired units at its fossil plants.

The fossil plants themselves face an uncertain future as tougher air quality regulations make it costlier to operate some plants that would need expensive scrubbing equipment.

Some observers believe the end is approaching for coal as a viable fuel source. A Jan. 25 story in the London Financial Times, headlined "The Death of U.S. Coal," examined the possibility that tight new Environmental Protection Agency restrictions on sulphur dioxide emissions will push utilities to start abandoning fossil plants as a source of electrical power. A July 19 story in Forbes magazine reported that Edison International already has shuttered two coal-fired plants near Chicago because of the regulations.

"I think the trend is going to be away from complete dependency on fossil fuels," said Chuck Laine, president of the Tennessee Mining Association. "But as alternative fuels are still not fully ready, it is going to be a while before coal is replaced."

According to the Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, coal mining got its start in Tennessee during the 1840s, mostly by blacksmiths who used coal in their shops. Large-scale mining didn't get going until after the Civil War, but by the 1880s coal mines employed about 4,000 people working above ground and 3,400 below ground. By the early 1900s, there were 85 coal companies in Tennessee and by 1919, the industry had reached a peak of 145 mines in Tennessee. Major mining areas were Campbell, Anderson, Scott, Claiborne, Morgan, Hamilton and Marion counties.

Coal mining in Tennessee hit a peak of production at 11.2 million tons in 1972, although at the same time employment was dropping because of increased mechanization. The development of new machinery made strip and auger mining profitable and by 1975, 60 percent of the state's coal was strip-mined. However, by the early 1990s the number of coal-mining operations in Tennessee had dropped by two-thirds, the number of workers by three-fourths and the value of shipments by two-thirds.

Today, coal mining companies employ about 1,500 people across the state, paying an average annual wage of about $40,000, according to the mining association.

Currently, about 10 coal companies operate in Tennessee, Laine said, adding that "there used to be about 20 in the state, but as costs went up, they combined."

A different look

TVA's board of directors sat silently Aug. 20 as the federal utility's president and CEO, Tom Kilgore, went through a Power Point presentation on a strategic vision to guide the agency's energy policies. It would help move TVA in the direction of greener energy sources and away from reliance on coal as a primary source for producing electric power.

Under this vision, by 2015 TVA would meet 1,900 megawatts of its energy needs through energy efficiency and demand response measures, 1,140 megawatts through nuclear power and 1,000 megawatts through gas. Also by 2015, TVA would eliminate 1,000 megawatts of power production by coal-fired plants.

Five days later, TVA took the first step toward this goal by announcing it would idle nine coal-fired power units at its Shawnee, John Sevier and Widows Creek fossil plants to reduce its coal-based power generation by 1,000 megawatts over the next five years.

TVA and other power providers are facing new EPA regulations that would amount to reducing sulphur dioxide emissions from fossil plants by 50 percent by 2015. This would require fitting pollution-control equipment known as scrubbers, which can cost millions of dollars. According to EPA figures, besides capital costs that can vary, operating scrubbers can cost from $200 to $4,000 per each ton of pollutant removed. The plants at which TVA is idling coal units are older and do not have scrubbers - fitting the profile of plants other utilities are closing because it is not cost effective to fit them with scrubbers.

Gary Brinkworth, TVA senior manager for new generation and portfolio optimization, said he doesn't know the cost TVA faced to add scrubbers to those plants, but he said the expense was a major part of the decision to idle the units.

Brinkworth was involved in developing TVA's Integrated Resource Plan, which is a long-range power production plan that looked at possible economic and regulatory scenarios and develop strategies. It generally called for more reliance on nuclear power and other means such as green power and less on coal. But Brinkworth said TVA doesn't foresee abandoning coal as an energy option, even in the most extreme scenario.

"We are still looking at coal playing a role," he said. "What we see us doing is relying on different types of power generation - nuclear, renewable, gas-fired - but we are still maintaining our coal fleet. Even in the most aggressive of the scenarios, we still maintain half of our coal fleet."

According to analysis by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, TVA's actions follow a trend across the country as utilities idle coal units or close fossil plants. The coal and utility industries are closely linked. More than 90 percent of the coal consumed in the United States is used to produce electricity, and the electricity produced from that coal accounts for almost half of electricity used. TVA generates 51.8 percent of its electricity from coal.

It is not clear how much TVA's move away from coal will affect Tennessee coal companies. Brinkworth said. TVA buys coal from all over the country, not just in Tennessee.

Not all Tennessee coal companies sell to TVA, either.

Dan Roling, president and CEO of Knoxville-based National Coal Corp., said TVA's decision to reduce use of coal will not affect his company as TVA is not one of his customers.

National Coal does seem to fit with a trend being driven by utilities, however. The company announced Sept. 28 that it is being acquired by West Virginia-based Ranger Energy Investments. According to the EIA, the restructuring that many utilities are undergoing because of the economy and new regulations is putting financial pressure on coal companies, pushing smaller companies out of business and leading larger ones to pursue mergers and acquisitions.

In general, coal production and consumption are decreasing across the nation, according to the EIA. In 2009, production decreased 8.5 percent while consumption decreased 10.7 percent. The decline in production was the largest since 1958. The Appalachian region had the biggest decline among coal-producing areas, with a 13 percent drop - the biggest in 50 years.

Eastern Kentucky produced the most coal in Appalachia that year at 73.4 million tons; however, this was an 18.7 percent drop from the 90.3 million tons it produced in 2008. Tennessee, one of the smallest coal producers in the region, accounted for 2.1 million tons of coal in 2009 - a 10 percent decrease from the previous year.

Still mining

There is still growth in the Tennessee coal industry, however. In June, Vancouver, British Columbia-based Thelon Capital Ltd. announced it was acquiring 6,000 acres in Campbell and Claiborne counties that it plans to develop as the Jellico Coal Project. The company estimates the property, part of which has already undergone surface mining, will yield 12 million tons of high-quality metallurgical coal.

Some coal industry observers believe development of carbon capture and storage technology, which involves capturing and storing the carbon dioxide from coal to greatly reduce emissions, may change the picture for coal. Progress has been slow, however.

A demonstration project by the multinational consortium FutureGen Alliance in Mattoon, Ill., stalled last year when two major utilities pulled out. However, the consortium announced Sept. 28 it had signed a $553 million cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of Energy to build a commercial-scale power plant.

Laine said something like carbon capture and storage technology will be necessary to keep coal a viable energy source in the future, but he and Roling both said the technology is just not there yet.

Robert Shelton, director of the Energy and Environment Policy Program at the Howard H. Baker Center for Public Policy on the University of Tennessee campus, said carbon capture and storage has been shown to work on a small scale, but the technical, economic and social issues that would be involved with underground storage of carbon dioxide are not well understood.

"And we are talking about disposing of massive amounts of carbon," Shelton said.

While he is not optimistic about the future of coal, Roling said its death has been predicted before. In the 1960s, the thinking was nuclear power would replace coal, but the Three Mile Island nuclear power incident in Pennsylvania and then the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Russia changed that. Shelton said that despite predictions of its decline, coal remains the mainstay of electrical power production. However, there are too many uncertainties now to predict coal's future, he said.

Shelton named a host of questions that need answers: Will the government establish a carbon tax and if so, will carbon capture and storage allow utilities to avoid it? If that happens, will communities accept the storage of carbon? Will the discoveries of new shale gas resources lower the price of natural gas and make it the preferred fuel alternative, displacing coal?

"Will the necessary policies be adopted to make nuclear a feasible alternative and will the public accept more nuclear plants on a large scale?" he said.

Will advancing technology make wind and other green alternatives more feasible?

"Some of the uncertainties can be resolved by transparent and decisive policies being adopted by the federal government and some will have to be removed by the market," he said. "Until some of the uncertainties are removed, coal and the alternatives to coal are frozen in place."

0 comments:

Post a Comment