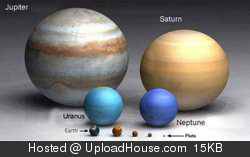

Well, take a look at this picture. This shows five important nuclides plotted against each other, with their size determined by their “barns”. You can see that one of them is absolutely HUGE.

That is xenon-135, as far as I know, the nuclide with the largest cross-section to absorb thermal neutrons.

Next on the list of trouble is samarium-149, which is really big, but not nearly as big as xenon-135. Again, to the best of my knowledge, samarium-149 is number #2 on the list of trouble.

For comparison purposes, I show the relative cross-sections of three fissile nuclides, uranium-233, uranium-235, and plutonium-239. These three are fuel in a nuclear reactor, and the bigger these are the better when it comes to making reactors small. By most descriptions of cross-section, U-233, U-235, and Pu-239 have big cross-sections, but you can see that they’re pretty small compared to Xe-135 and Sm-149. Like comparing the inner planets to Jupiter and Uranus.

Why does this matter? Because if we had it our way, we wouldn’t want any Xe-135 or Sm-149 gobbling up neutrons in our reactor. Neutrons they eat are neutrons that we can’t use to make energy by splitting fissile nuclides like Pu-239 or U-233.

Xe-135 has two major differences from Sm-149. The first is that it is radioactive. It goes away if you leave it for awhile. It has a half-life of about nine hours. Sm-149 doesn’t go away. It is not radioactive. It is stable.

The other difference is that xenon is a noble gas, and is easy to remove from a fluid fuel like the salts that we want to use in liquid-fluoride reactors. So getting Xe-135 out of the mix isn’t terribly difficult. Samarium on the other hand is pretty challenging to extract from the salt mixture. It’s one of a family of elements called the “lanthanides“, and they all have very similar chemical properties to each other, because their outermost electron layer (the one that does all the chemical bonding) is the same while they fill up the inner electron layers as you progress up the list of lanthanides. So it’s hard to come up with a chemical process that is particularly good at picking off samarium without picking off all of the other lanthanides at the same time.

0 comments:

Post a Comment